It was back in September 2018 when a DM from the awesome TENC (Team English National Conference) women appeared in my inbox asking me to lead a workshop at this year’s conference. I was stupefied at the thought that people actually wanted to hear from me. Keeping in mind, that this during the period when I was battling with my own perceived limits around my ability to speak publicly.

In complete honesty I panicked; I was both honoured and floored by the thought that such power-houses from the Team English community even thought of me in the first place. I immediately began to bat around a million and one ideas before I settled on two potential workshops:

- How to enthuse and encourage Pupil Premium students with the English Curriculum

- How to plan a SOL in a way that keeps you engaged in the process and positive about the final outcome

Focusing specifically on Pupil Premium and the English curriculum was exactly what I needed for my own professional development, especially given my current role as Pupil Premium Leader, as well as being a tricky area to pin down in terms of actual tried and tested strategies that you can provide staff with to implement in their own classroom settings.

Having been to a fair few conferences and optional CPD sessions, I have fairly consolidated views on what I, personally, think makes a successful workshop. When I attend a workshop I want to either walk away feeling inspired and motivated to make a difference in education or to walk away with actual, effective strategies that I can implement into my practice when I get back to my school. With this in mind, it was important to me to give people something they could use that went beyond the intangible ‘build good relationships’ but to also be brutally honest about how we perceive Pupil Premium students.

So, on Saturday 13th July 2019 this is what I had to say…

The aim of my session was to develop a deeper understanding of disadvantage and how it can affect students’ experience of education differently, including how to alleviate misconceptions and address our unintentional stereotyping. I also gave a little insight into my background and why I am so passionate about improving social mobility for our disadvantaged students.

It was imperative for me to share this amazing introduction from Ian Gilbert’s The Working Class as it highlighted for me some of the misconceptions that I unconsciously held about students that I have taught over the years. It wasn’t until I began working at my current setting that I truly understood the meaning behind deprivation and the profound impact it can have on the young people we have in front of us everyday. It goes without saying that we can become so overwhelmed by the day-to-day pressures of teaching that we can forget to evaluate the impact we, and our words, are having on those around us.

Dr Ceri Brown’s work on the binds of poverty is particularly impressive in its breakdown of the impact of poverty and how this can be separated into three separate binds:

- Material Deprivation

- Alienating Culture of Education

- Social Capital

As teachers we are limited by the confines of our profession so being able to positively impact material deprivation is nearly impossible. Yet, in spite of this, we can tackle the other binds of poverty through a few straight-forward approaches both in our classrooms and in the wider school culture. In order to do this I would propose focusing on the following areas:

Reframing our societal views

To even begin to approach this area, we need to accept the fact that we are the product of an education system that is inherently middle class; with that comes the responsibility to honestly evaluate and reflect on our views both holistically (see the above example from The Working Class) and on an individual basis. It is, without question, extremely uncomfortable to do this, if you do it properly, because to be a part of this professional we undoubtedly have strong moral and ethical values. The very idea that we may have slipped off the tightrope and believe, unintentionally, in some of the stereotypes is frightening. But, it is natural and it is hard work to address and reform some of these views. What I mean by this is simple… you know that year 9 class, the one with Billy in it? The one that is a nightmare, every time, for no apparent reason? Well, that’s that unintentional stereotyping creeping in. Don’t worry, I was nodding in agreement as I writing that too – I’ve taught that class, or so I thought. But it is in fact these voiced, or unvoiced, views that can be dangerous, not just for our students but for those other teachers in the staff room that we share these negative opinions with.

This in turn seeps into how we interact with the community, something I think we seriously undervalue as a profession. If you take nothing else from this blog, please take this piece of advice: go out into the community, whether that be on your attendance bus or simply for a home visit, and see where you students are living. It can be quite an eye-opener.

Routines, Language and Expectations

If you haven’t heard the buzz around cultural capital as of late then I honestly don’t know what rock you’ve been living under… Since the new Ofsted framework, this is the hot topic; frankly, it shouldn’t be anything new but it is, sadly, something we’ve forgotten to prioritise in the drudge of exam pressure and Progress 8 measures. However, Bourdieu’s work , on the different forms of capital are particularly interesting when considering the impact that a high cultural and social capital can have for our students.

Further to this, thinking about how we support the development of a high social capital is closely linked to how we demonstrate our expectations in both a behavioural and skill-based sense. In addressing this, I would first recommend reflecting on your behaviours/attitude in different situations with different groups of students contemplating the unintentional stereotyping taking place, how can you refocus your actions and language to remove this and build on social capital? Following on from this, the use of demonstrating skills with a class, whether that be with an iPad or visualiser, should not be underestimated – students flourish when they are provided with or given the opportunity to help build examples, verbalising this process allows metacognition to develop alongside much needed oracy skills.

Bridging the Gap

I am particularly vehement when sharing my views on the idea of low aspirations in working class communities; it’s not only insulting but detrimental to insinuate that long-term unemployment equates to low aspirations. In fact, we tend to find that students from the most deprived background understand the need for high aspirations more so than their counterparts. Instead of fuelling resources into building aspirations, we need to tap into and understand what our students want to achieve and then harness that by bridging the gap between where they are now and the paths, courses and/or choices they need to make in order to reach their desired destination. A powerful tool in doing this is bringing parents into the dialogue and ensuring they understand how to help their child get there, whilst addressing those misconceptions about what they can achieve.

Without a shadow of a doubt, the road to success for many of our economically disadvantaged students, although paved with good intentions, are often littered with barriers that seem almost impassable – barriers that, as a society, can be perceived as self-imposed, genetic, just how it is.

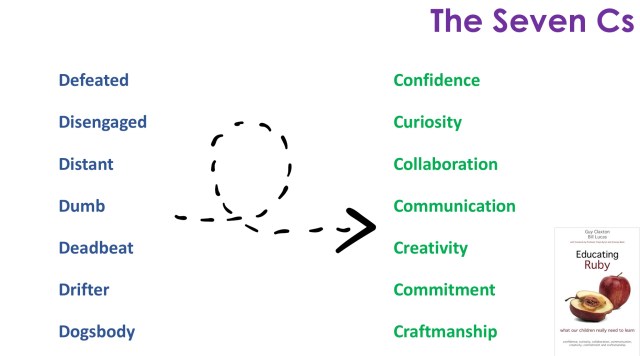

Students who face these barriers often display the ‘Seven Ds’ of educational disengagement (see Educating Ruby by Claxon and Lucas for more on this) and as educators it is our responsibility to turn these ‘Seven Ds’ into the ‘Seven Cs’ – we can do this by asking some fundamental questions:

- Defeated to Confident – are students able to access the material that has been provided? Is the curriculum achievable?

- Disengaged to Curious – are we fostering curiosity of why we are where we are in our literary history and language?

- Distant to Collaborating – are we providing the tools to problem solve?

- Dumb to Communicating – are we fostering oracy skills?

- Deadbeat to Creative – as a teacher who, although drama trained, shies away from drama-styled activities, are there lessons to be learned by moving outside of our comfort zones?

- Drifter to Committed – are they invested in their own success? Is it achievable?

- Dogsbody to Craftsmanship – are our students merely performing or are they actually learning?

Whilst fostering the ‘Seven Cs’ in our individual classrooms is important, we must also be willing to address them, at department level, within the English curriculum.

To begin with we need to look at the texts that we are using to heighten our students’ cultural capital. Are we merely sticking to where we feel comfortable and teaching what we know or are we using these texts as a foundation to a deeper understanding of the world in which they live in? I purposefully make the distinction of their world here because the knowledge that we have acquired over our life time is enlightening in terms of our views and perception of our society; the young people we have in front of us are not yet at that stage. Consider this, are you developing a curriculum around the community in which you serve or in spite of it?

With that in mind, I would urge the reconsideration of the adaptability of our curriculums and schemes, because not all children will have the same access to your classroom. Here, I am specifically talking about those students who don’t have the same opportunity to attend 100% of the time. Whatever the reason, the PA cycle exists for that child – the habitual absent and poverty can lead to unemployment which then impacts their future family, leaving their family in poverty and falling into the trap of habitually absence – restarting the PA cycle. We are fortunate enough to be in a position to alleviate some of this pressure by ensuring that skill is at the core of each scheme, ensuring practice and refinement have a heavier weighting, allow a child to pick up and apply the same skill at different points. This works perfectly alongside schemes that allow for creativity to flourish – it is ridiculously easy for us, as English teachers, to fall into the trap of writing essay after essay, but in that monotonous series, if overly done, we lose the passion and creative spark that our beautiful subject lends to. It is in this creativity that we can develop craftsmanship.

It is vital that while we guide students to see beyond the boundaries of their own community, not to denigrate them but enlighten them.

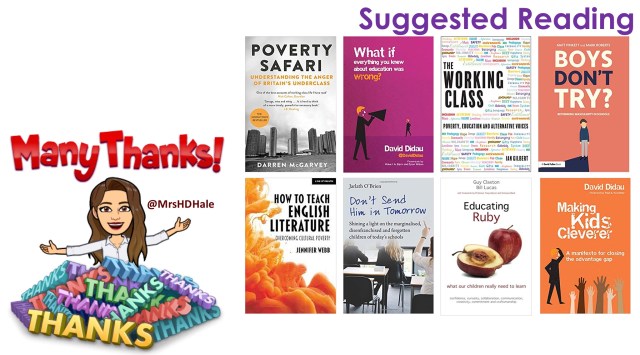

It goes without saying that there is an abundance of research out there that has helped form my perspective on addressing disadvantage and how that can be accomplished. Above are few EduBooks that I believe are a great start to establishing a strong understanding and honest reflection on how we can begin to support students from disadvantaged backgrounds and battle the atrocious impact that the binds of poverty can have on our students.

To finish off, below is a clickable link to the tweet I sent out with the presentation slides, along with a subtweet that has the link to the Crime Fiction SOL I referenced when I explored creativity and craftsmanship in the English curriculum.

Excellent piece of work, true insight by a very understanding professional!

LikeLiked by 1 person