The Naïve SENDCo Series

As dawn broke through the early morning horizon, the Naïve SENDCo retreated to the troop accommodation to share battle wounds and strategy.

As an educator, passionate about my field, there is nothing more fulfilling than galloping off to conference at the end of the working week, where there is the opportunity to talk unfiltered about research and movements within the world you’ve chosen to exist in.

It was a scorching hot Friday in early June when I packed my bags and loaded them on to my trusty stead before heading off to the We Collaborate conference, thankful for the grace of air conditioning in anticipation for the five hour journey. A conference led by an amazingly supportive friend, who permitted me the opportunity to bring with me my little warrior in the making, and the helpful hands of my partner, on hand to supply the snacks and distraction from disrupting my talk.

I’m sure we are all versed in how the battle strategy does not always match the dynamic plan in the midst of the chaos. This is why I thought it pertinent to give you what is meant behind each slide of my beautifully presented, even if I am biased, PowerPoint battle strategy.

Without further adieu…

I suppose we should start with the question: why be so dramatic as to call it ‘Tales of the Naïve SENDCo?’

The calling of the battlefield pulled me into the role of SENDCo in the beginnings of 2023, heavily pregnant with my first born and finished with the preamble before the war of parenthood began. So, rather large and in charge, I naively waddled my way into a field I was wholeheartedly underprepared for.

I have forever had a strong work-ethic, being thorough in my application and strong-headed in my opinions. I have continuously prided myself on being knowledgeable and well-versed in my role, regardless of the accountability or responsibility.

SENDCo was a role I was vehemently adamant I would never do, because I simply didn’t know enough. How could I take on the weight of a child’s educational and holistic future if I was blind to the intricacies of their needs?

But, it seems that my stubbornness was the victim of the mistress of moral compass when a colleague convinced me I would take to the role like a duck to water… I suppose they weren’t wrong if the duck was legless, upside down, trying to use its wings to do the breaststroke, backwards. I was genuinely naïve in my thought that I would glide into the role as a hero, giving these wonderfully brilliant motivational talks to my likeminded colleagues, preparing everyone perfectly for the easiest fight of our lifetime.

Yet, in the raw and blinding reality of the role, my gliding demeanour stumbled at the first step into the field. I was instead, bombarded by the frankness that the role itself would seep with the perception of the haggard, outcasted, villainous witch of the fairy tale.

That strange creature that everyone is hesitant of, that just appears in the background of every scene asking for the humble villagers to buy her ‘delicious’ apples.

But the harsh morale of the story couldn’t be further from the truth.

Why am I telling you this tale of a role rather than giving you the practical, magical strategies you came here for?

I tell you this tale because frankly if you don’t understand the reality of your SENDCo, you’ll struggle to understand the intricacies of SEND provision.

I can fondly recall in one of my first jobs in education, an assistant principal who happened to oversee SEND (he may have even been the SENDCo, who knows), who you could play ‘chunk it’ bingo with during every staff briefing, CPD and meeting. I mean simple right, just chunk it.

But it wasn’t until I became a SENDCo myself that I understand what he was trying to portray to the giggling gabble of geese at the back of the room – ‘make your room inclusive, teach every student as if they were a student of SEND and you will subsequently support every student of SEND. There is no magical formula, just common sense good practice.’ You know, the age old ‘quality first teaching’ that is the solution to all things education? Remember in primary school when you would be given blue roll, no matter the ailment?

Naively, I galloped into the role, head down, spear sharpened, ready to lay down the law. But it was the law that won that battle – a battle I will notably mention, left me befuddled and disorientated for weeks.

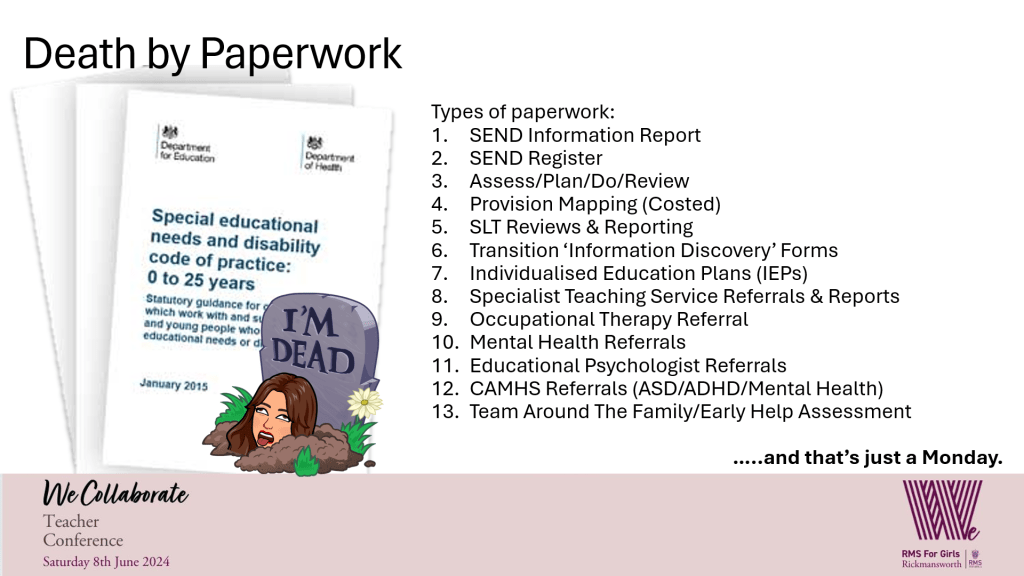

The paperwork, and the legislation around the paperwork, was mind-bending. To begin with there were three pieces of legislation that are the most important when it came to ensuring we were compliant, aka acting lawfully… no pressure. These government-bestowed pieces of guidance/legislation included:

The Children and Families Act (2014)

Thanks to the wisdom of Gary Aubin, I knew I needed to delve straight into the histories of ‘Part 3: Children and Young People in England with special educational needs or disabilities.’

The SEND Code of Practice: 0 to 25 years (2015)

This one was a little trickier at 292 pages. But, at least I could skip to Chapter 1 (Introduction), Chapter 2 (Impartial Information, Advice and Support), Chapter 6 (Schools) and Chapter 9 (Education Health and Care Needs Assessments and Plans). So, not too much reading by candlelight.

The Equality Act (2010)

Finally, Part 2 (Protected Characteristics) and Part 6 (Education and Schools)

Reading done, there I was ready to take up my position at the helm of the ship and guide my teachers through the misty mornings and treacherous swell of the yawning oblivion of half term three. That however, was only the early dawn of the paperwork that would ultimately turn this once battle-ready warrior into a tattered hag, clinging onto the last remanence of her forgotten youth.

A cautionary tale for you, young warrior, this is just the surface of the paperwork that a SENDCo must complete, review and adjust on a regular basis. Each aspect of the paperwork above requires the SENDCo to know the ‘admin’ information (name, DOB, address, parental consent), as well as their progress (attendance, behaviour, academic attainment, round robin) and their background (family history, primary school information, mental health needs), as well as the intricacies of their SEND identification.

But, as always, a little laugh at my expense: At 37 weeks pregnant, angry, large and most definitely in-charge, I received a phone call from a CAMHS worker who began to tell me how I had personally failed a child (having known them for just 2 and a half months) because I was not meeting his needs as it was clear that he was ADHD. Well, poor Esta got told what for and I proceeded to inform her that she had no right to diagnose a child, she was not a clinical psychiatrist… turns out she was in fact well within her right.

Yet, here we, the lone SENDCo beguiled by the weight and burden of the room, are on the precipice of defeat when everything starts to click into place. Reminiscing of a time long gone…

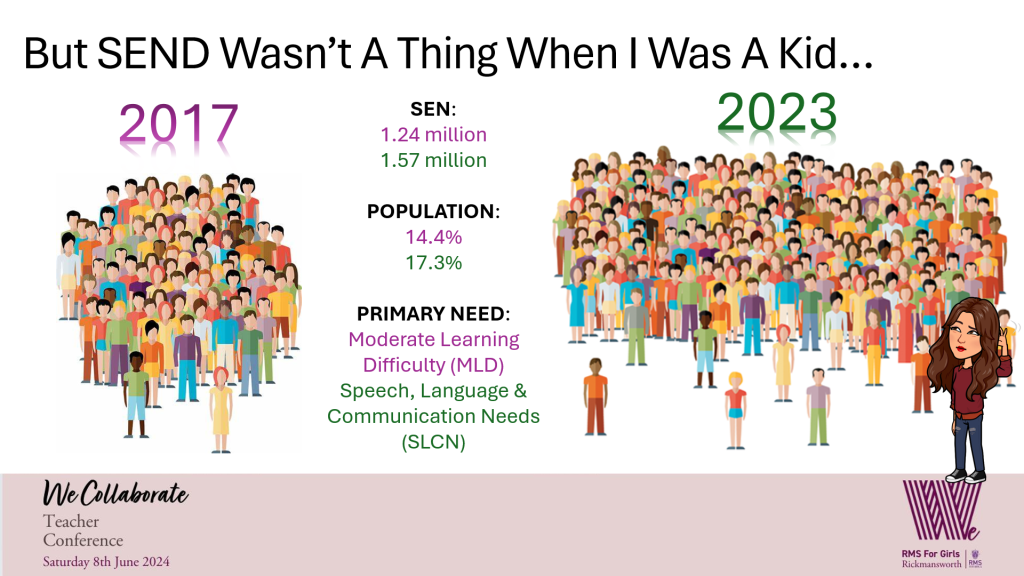

In 2017, 1,244,255 students in schools across England were identified as having SEN. This was the first time since 2010 that the figures had risen from the previous year.

Over several years, the national picture for SEND appeared to be decreasing by number but stable by percentage. 2016 and 2017 brought about the matrimony of death and destruction, with a series of violent attacks spreading across the UK, and it was in these years that the beginning of the rise of SEN was observed.

MLD symptoms to SENDCos became what the Trojan Horse was to King Priam, a thoughtful gift, in the way of identification, that would later prove to be an inextricable nightmare. Easy to identify and a catch-all need type, right?… developmental delay, behavioural outbursts due to learning difficulties, low self-esteem, short attention spans… What an easy way to explain what was being seen on the battlefield of education.

But, research indicates that the label of MLD is often is often used in an over-generalised way in schools as a way to categorise low attaining students for additional intervention.

(Norwich, B., Ylonen, A., & Gwernan-Jones, R. (2012). Moderate learning difficulties: searching for clarity and understanding. Research Papers in Education, 29(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2012.729153)

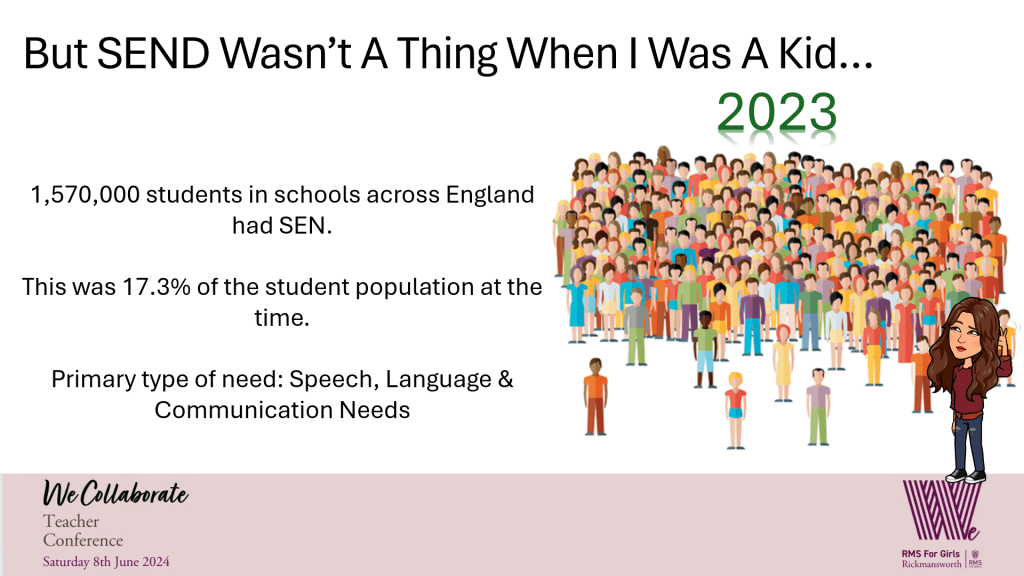

The mythical age of 2017 became the whispers of legends, with the dawn of 2023, bursting into the tale with 1.57 millions students in schools across England being identified as having SEN. In just six years, the figures had stretched across caverns, almost measureless to man (one for my English lot), by a 2.9% increase.

It is without question, interesting and not at all surprising that the primary need is SLCN, particularly given the trials and tribulations over the last four or so years. This need type, more specifically pragmatic language difficulties is most prevalent in the current year 8 and year 9 students, also referred to as the Covid cohort.

Like all good fables, we are shaped by the stories before us, and although 2017 seems like a land before time, it’s overuse of MLD categorisation caused a malignant infection to grow under the surface, particularly around transition points. Too often as a SENDCo, I feel the burning itch of the foul sore gnawing away, when the CTF file drags the need type kicking and scrambling to my SIMs door: MLD.

This prophecy talks in riddles and is equivocal in nature. It is specific, yet general – giving no insight into the needs of the student. A Trojan Horse, leaving nothing but pieces to arrange and useless information to bury, deep within a file. An agonising fresh assault of identification and assessment must then ensue to determine the battle plan for that student, to figure out how to get them through the Forgotten Forest, over the Gorge of Misdirection and Misunderstanding. and given passage through the Gates of Effective Support.

To label or not to label, that is the question: Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous knowledge, or to take arms against a sea of troubles and by opposing end them.

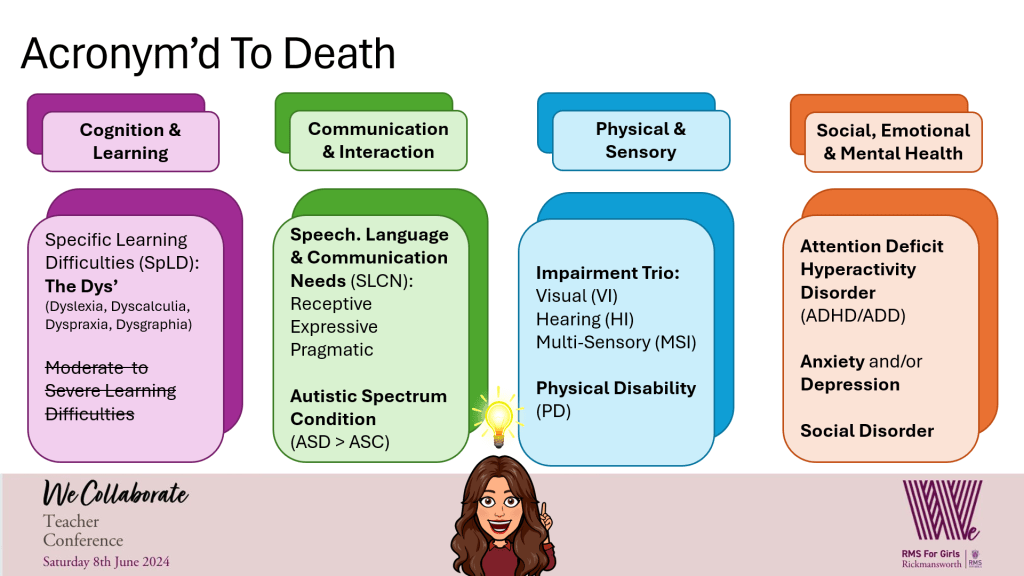

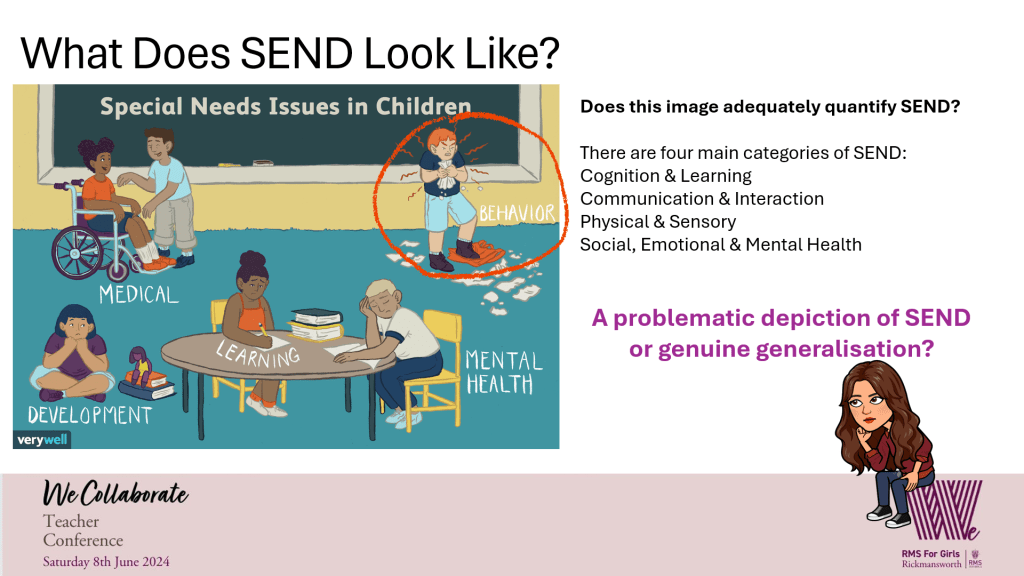

In the realm of SEND we live precariously on the edge of the importance of identification and the fragility of labelling. Whilst it gives us a way to start the conversation of support with those not versed in the art of acronym, it can also acts as a barrier to meaningful conversation.

Let me elaborate. A young solider was helpfully identified as having dyslexic tendencies, information that was shared with his forebearers and teachers. The teachers used this information to apply the skills that would be fortuitous for him in his KS3 to KS4 journey. But for his forebearers this created a sense of panic, a quizzical desire to have him diagnosed officially. If they didn’t do this, it was a perceived failure on their part. This created a minefield in the midst of the conversation, rather than letting the fruits of the assessment and identification process flourish into the branches of support.

But, should I have not shared this information? Of course not. Yet, here we are left in a tangle of confusion and fear.

I would argue that, whilst the label can be a source of greatness for one it can be a tool of catastrophic downfall for another. I cannot give you an easy solution as to how to traverse this difficult path, but only to tell you to tread cautiously and with forethought, as hindsight is no friend of yours.

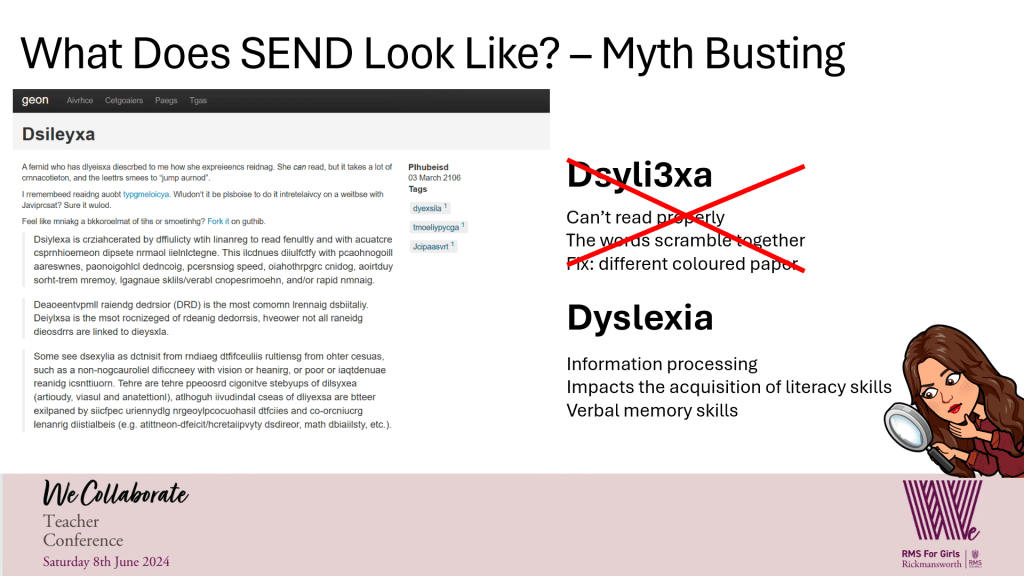

In 2016, Victor Widell created a website to demonstrate to those who did not have dyslexia, what it looked like, following a conversation with his friend. Whilst, in theory this is a brilliant idea and a brilliant way to bring the conversation of dyslexia to the round table, it is also problematic.

This simulation leans into the impression that dyslexia is about words jumping about on the page when in actual fact it is much more.

Dyslexia is the original misunderstood need, in my humble opinion. To begin with, it is often thought to be curable when in fact it is one of the lesser discussed neurodivergences. From there, the fix-all thrown at it seems to be a coloured overlay, never mind the consideration of additional processing time, support in sequencing events, or the proper combination of written and verbal instructions.

This is the perfect example of how the power of identification and labelling can be misjudged when harnessed incorrectly.

Here, I digress and tell you a tale of a child misjudged but not necessarily misidentified.

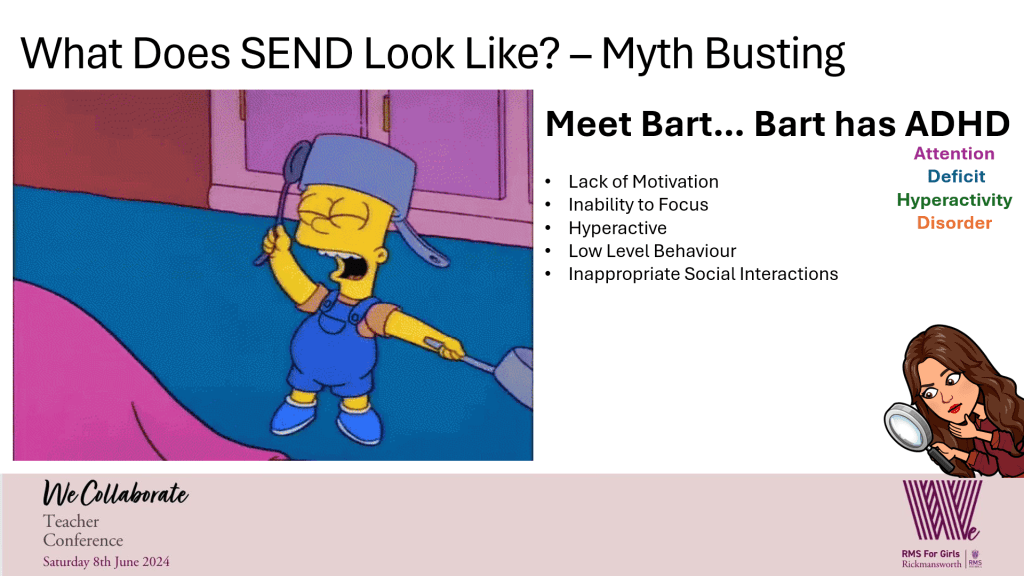

Meet Bart, Bart is your stereotypical white, British, boy diagnosis of ADHD. Bart is not a great example of what ADHD looks like, yet as a society this is what we have become comfortable with associating with the label.

As a society we deem that: most students will grow out of ADHD, that boys are more likely to have ADHD, and that everyone has a little bit of ADHD.

ADHD is a neurodivergence which means that the brain is wired different to that of a neurotypical brain; not lacking in attention or motivation. Research actually indicates that ADHD is hereditary and therefore we observe trends in symptoms throughout a family unit.

Women are less likely to be diagnosed with ADHD due to societal expectations and therefore unwittingly masking throughout their childhood – teenage girls’ symptoms will often be overlooked or are often described as being anxiety due to a desire to over-achieve: forcing them to conform to a world that expects more of them while asking for less; deeming them broken when they become overwhelmed by their need to over-achieve, leaving a history of tattered misfortune in the wake of a late diagnosis.

Off the rant of my high horse, where do we go from here. What practical solutions do we give the swarm of desperate teachers thrashing on the gates of our knowledge?

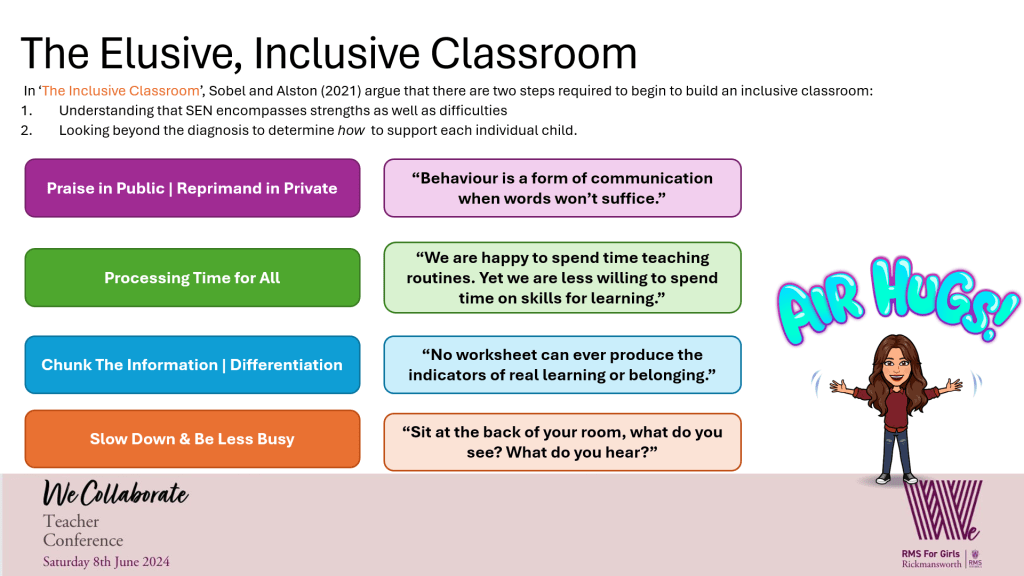

Inclusivity does not mean being overtly energetic, fluffy round the edges and eager to give air hugs. Inclusivity is about looking beyond the label and considering the needs and strengths of all children.

When we give students feedback, we give them strengthens and targets, whilst the target is the main focus of the feedback, we stress the importance of taking the guidance of the strength into consideration as well. We tell students to lean into their strengths.

So why do we look at SEND any differently? Simple, time.

As SENDCos we bear the burden of perceived power and wisdom. We are seen as one who can bestow a diagnosis, although we cannot. One who knows all when it comes to saving children who have been left behind, although we do not. One who has the power to fix every SEND, although we cannot and do not.

On this, I leave you with the words of Galadriel: ‘to bear a ring of power is to be alone. This task was appointed to you. And if you do not find a way, no one will.’